Regardless of wether in the broiling, effervescent December of Rio de Janeiro or the crisp and cosy dutch winter, I’m amazed to see how some universal end-of-the-year customs prevail. The nights illuminated by warm Christmas lights, the joyful anticipation for the year to come, and especially the mellow scents of roasted chestnuts, cinnamon and baked goods give a pleasant sense of belonging no matter the geographical location. That’s why in my mind December asks for pie, and especially apple pie. Thankfully, Sagan, the ingredients to make homemade apple pies can be easily acquired in any local market, and we do not need to first invent the universe. But—let me tell you this—that is something I would like to explore.

And with this sweet introduction I wanted so bad to put on paper I can segway into the actual topic of this post: my research work. Alfie’s last blog post inspired me to share a little bit more on the research I’ve been working recently and the main topic I want to tackle during my PhD. Or, at least, what my plans are for the near future, since three and a half years are simultaneously a heartbeat and an eternity when it comes to science.

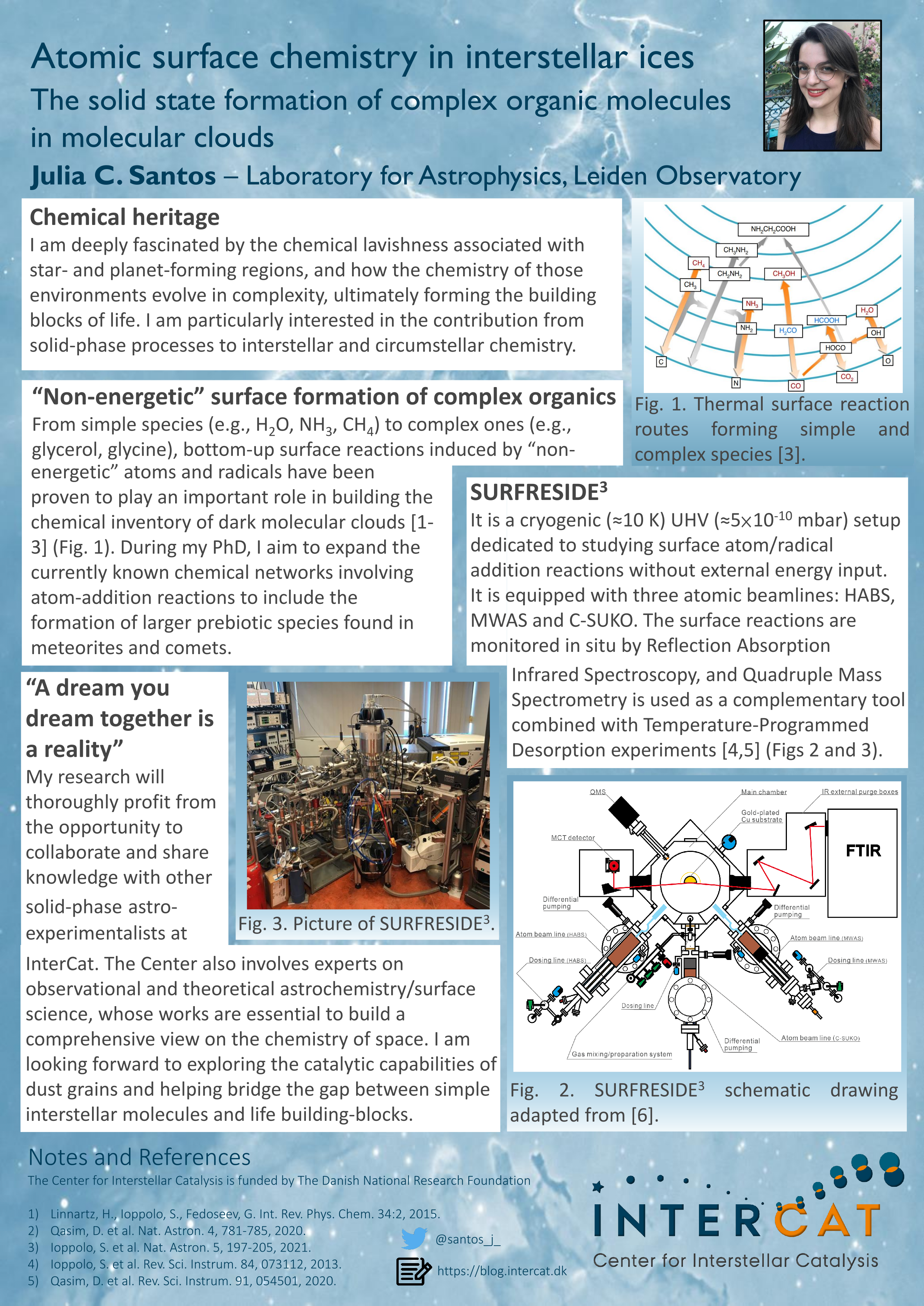

Long story short, I am fascinated by the chemical lavishness associated with star- and planet-forming regions, and how their chemical inventory evolves in complexity, ultimately leading to the building-blocks of life. In my PhD, I want to explore this connection by studying in the laboratory the chemical reactions that happen in interstellar ices, and how those can lead to the formation of complex organics and prebiotic molecules.

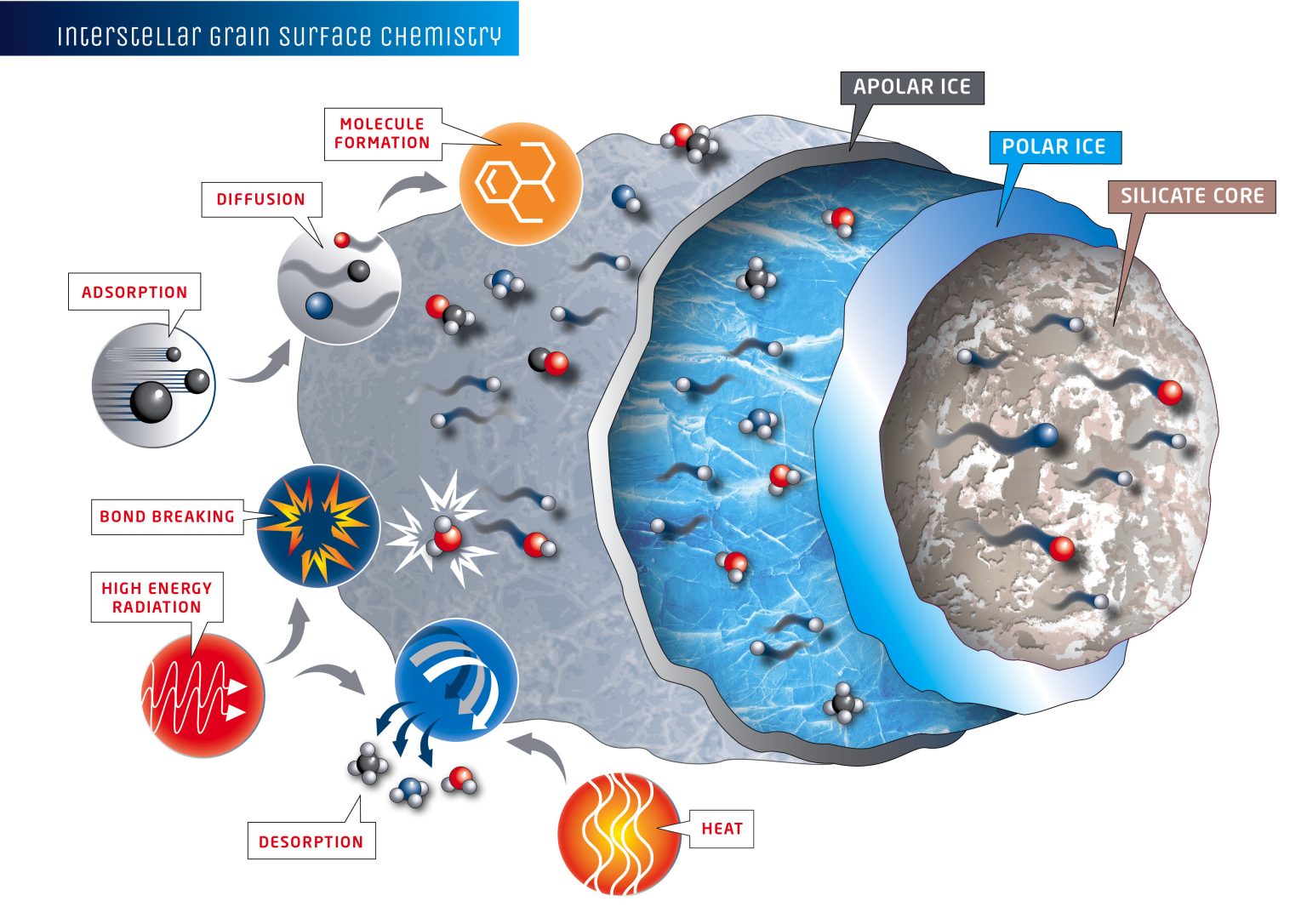

The different types of surface chemistry that happen in interstellar ices and lead to the formation of complex organics. Image credit: Jenny Leibundgut of Leibundgut Designs, Center for Space and Habitability (CSH).

Right now, we are finishing-up a project on the formation of methanol (CH3OH) in space. This molecule plays an important role in the chemical network of the interstellar medium, and that’s why it’s important to understand its chemistry in as much detail as possible. Accordingly, we have performed experiments in the ultra-high-vacuum setup SURFRESIDE3 in Leiden to create analogues of the interstellar ices rich in CO and to see how it interacts with hydrogen atoms to form methanol. In the end, we were able to employ a quantum-mechanics phenomenon called the kinetic isotope effect to assess the contribution from different chemical routes to forming CH3OH.

Me and my daily companion, SURFRESIDE.

I couldn’t agree more with Alfie when he says how enjoyable it is to see our own scientific progress. It would be hard for the early-2021 Julia stuck at home unable to travel to Europe to believe all we’ve accomplished in the last couple of months. One can’t help but wonder which scientific adventures the next year will bring, and I’m looking forward to them.